1922: THE STORY OF MANKIND by Hendrik Willem Van Loon

We live under the shadow of a gigantic question mark.

“Often the ‘sightseers’ and even those included in the nucleus did not know why they had taken part in crimes the viciousness of which was not apparent to them until afterward.”

-from The Negro in Chicago: A Study on Race Relations and a Race Riot (1922)

In 1922, a subcommittee of the American Library Association met in Chicago to review the results of a poll they had sent to childrens’ librarians across the country. Based on the poll results, they awarded the first-ever John Newbery Medal for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children to the nonfiction history book The Story Of Mankind by Hendrik Willem Van Loon.

In 1922, a different committee in Chicago reviewed different data and published a different document. The governor of Illinois had appointed a team to write The Negro in Chicago: A Study on Race Relations and a Race Riot; the report was commissioned in response to brutal race riots that had torn apart the city in the Red Summer of 1919. In the Great Migration of the nineteen tens, fifty thousand Black Americans had moved into Chicago, and the vicious inequality and segregation and open racism in the city had exploded into sustained violence at the end of the decade. The governor’s committee was charged with understanding and articulating why the riot had happened so that we could prevent something like it from ever happening again, which meant that they had to understand and articulate just how bad things were for Black Americans living in Chicago in the nineteen tens.

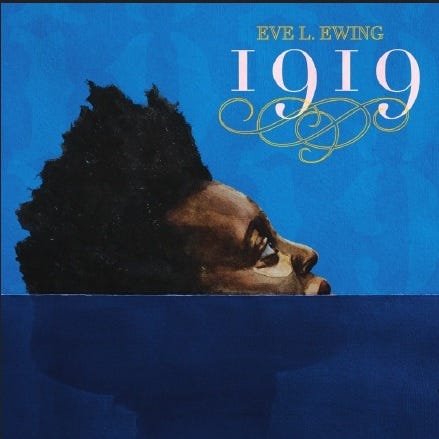

In 2019, a century after the riot, one of Chicago’s current Renaissance women, Eve L. Ewing - a sociologist at the University of Chicago, a poet, an author/scholar, and an occasional writer for Marvel Comics - published 1919, a collection of poetry based on her reading of the Illinois commission’s report. Ewing’s poems are interspersed with snippets from the committee report and, to state the obvious, looking back on a once-famous but now-forgotten race riot by writing a book in 2019 seems awfully prophetic. And a lot of these poems are devastating in different ways, but the most profound one, for me, is “sightseers”, introduced by the quotation at the top of the piece. I don’t want to reprint the whole poem because I don’t own the poem and you should just read all of 1919 anyways (available now from Haymarket Books! At the time of this writing, the ebook download was free!), but Ewing opens with:

“just this once I hope you’ll forgive me

For writing a somewhat didactic poem

I just didn’t know how else to say

that we live in a time of sightseers

standing on the bridge of history

watching the water go by

and there are bodies in the water”

Remember in 2020 how everyone thought the world was falling apart because of the plague and the protests and the elections? I don’t know if you remember, but we also thought the world was falling apart in 2019. Our government was shut down for months because of our wet toddler president and we were in the third year of that presidency and there was an impeachment investigation and more mass shootings and presidential crises in other countries and there was almost a nuclear war between India and Pakistan and Notre Dame caught on fire and there was a different plague (the second-deadliest Ebola outbreak in history) and a different massive protest (1 million people in Hong Kong) and a different disaster throwing smoke into the air (the Amazon was burning) and and and a million other things and then everything got worse later. And in Ewing’s poem, this was the “time of sightseers”, people just kind of staring at it bemused and looking up at the tower of empire because “they find the lights enchanting/they meet up on the weekends/they have picnics in the plaza of the tower/that has our children in it.” And she begs us to forget about how entertaining and surreal everything is, to forget about how pretty the lights look:

“because there are children in the tower

there are children in the tower

there are children in the tower

and they are dead already”

There are so many places you could go with The Story Of Mankind, the first-ever Newbery medalist, covering the history of humanity from the first neanderthals to 1921. You could, for instance, start with the bizarre and inexplicable 1957 film adaptation of the book - and again, this is a nonfiction history book - that fictionalizes a trial of humanity, in front of God, prosecuted by Satan, who is played by Vincent Price. Hedey Lamar is Joan of Arc. Peter Lorre is Nero. Dennis Hopper is Napoleon. This movie is real and I almost bought the DVD to watch it for this essay. Also the Marx brothers are in it, so I guess it’s a comedy? Here’s some funny racism for you, again from a real movie that Warner Brothers made in 1957:

Another place you could start with this book is Van Loon’s introduction, a letter to his family in which he shares an anecdote about looking out over a city from a church steeple as a child, and hoping that his descendants can use his work to summit the tower of history and get the full view of what’s happening in their world:

“History is the mighty Tower of Experience, which Time has built amidst the endless fields of bygone ages. It is no easy task to reach the top of this ancient structure and get the benefit of the full view. There is no elevator, but young feet are strong and it can be done. Here I give you the key that will open the door. When you return, you too will understand the reason for my enthusiasm.”

And, after you open with this quote, you can then dive right in to the dramatic irony of reading a child’s history book first published over a century ago, before the Great Depression, before the rise of fascism in Europe, before the development of nuclear weapons, or the mass production of the automobile, or televisions showing up in every home, or the creation of American suburbs and interstates, or factory farming, or not just the internet and not just microchips but the very concept of computers.

Another place to start would be to observe, and probably mock, Van Loon’s short-sightedness when it comes to picking and choosing which parts of history are “important”. He acknowledges that he can’t possibly cover every nook and cranny of history in what was originally a 466-page book1. But how he frames this up, at the end of his chapter on the Thirty Years War, is hilarious. Here’s how he starts:

“But before I tell you of this outbreak which led to the first execution by process-of-law of a European king [referring to the execution of King Charles I], I ought to say something about the previous history of England. In this book I am trying to give you only those events of the past which can throw a light upon the conditions of the present world.”

Ok, sure, let me just check and see what Van Loon writes immediately after that to see how he determines what’s important to the present world:

“If I do not mention certain countries, the cause is not to be found in any secret dislike on my part. I wish that I could tell you what happened to Norway and Switzerland and Serbia and China. But these lands exercised no great influence upon the development of Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. I therefore pass by them with a polite and very respectful bow.”

Ah, well, as long as the bow is very respectful. Yes, obviously I would love to cover all of human history, but I have to limit myself to what was important, and some of these people - get this - weren’t even European, so no, I’m not going to be able to make room for them here. Look, it’s a history book from the nineteen twenties. It’s incredibly Eurocentric and Christocentric, which makes it a popular choice for weirdo homeschool parents. Van Loon does have some opinions on the violence of the “Mohammedans” and clearly considers the founding of Christianity to be the most important moral and civilizational development in history. Which he’s allowed to do - and I guess, technically, I'm also supposed to think that? - but it feels weird in an ostensible history textbook. He also, twenty pages from the end of the book, just straight-up says he probably didn’t pull off what he was trying to achieve and probably should have just scuttled the manuscript altogether, which is a pretty incredible thing for any author to admit right as he’s about to finish his book:

“If I had known how difficult it was to write a History of the World, I should never have undertaken the task. Of course, any one possessed of enough industry to lose himself for half a dozen years in the musty stacks of a library, can compile a ponderous tome which gives an account of the events in every land during every century. But that was not the purpose of the present book. The publishers wanted to print a history that should have rhythm - a story which galloped rather than walked. And now that I have almost finished I discover that certain chapters gallop, that others wade slowly through the dreary sands of long forgotten ages - that a few parts do not make any progress at all, while still others indulge in a veritable jazz of action and romance. I did not like this and I suggested that we destroy the whole manuscript and begin once more from the beginning. This, however, the publishers would not allow.”

But I kind of get where Van Loon is coming from here. The Story Of Mankind is supposed to be this engaging read where the author does directly address the reader and expresses bemusement at the long unwinding tale of civilization and you’re supposed to feel like your grandpa is telling you a story about the ancient Greeks and the Tudors and whatever. But as Van Loon was writing this book, the Great War - a war with no good cause and no real logic to who won or lost or lived or died, as horrifying new ways of killing made their debut on the world stage, all of which Van Loon acknowledges in his final pages - was tearing through the world. In his words:

“The original mistake, which was responsible for all this misery, was committed when our scientists began to create a new world of steel and iron and chemistry and electricity and forgot that the human mind is slower than the proverbial turtle, is lazier than the well-known sloth…a Zulu in a frock coat is still a Zulu. A dog trained to ride a bicycle and smoke a pipe is still a dog. And a human being with the mind of a sixteenth century tradesman driving a 1921 Rolls-Royce is still a human being with the mind of a sixteenth century tradesman. If you do not understand this at first, read it again. It will become clearer to you in a moment and it will explain many things that have happened these last six years.”

It became very clear to Van Loon, during the six years he spent on a project celebrating the achievements and growth of mankind, that mankind was equipped and ready and willing to mutilate and destroy itself and most of us were just going to stand there and watch it happen. And so the tone of the final pages shifts significantly, as Van Loon moves from curiosity and bemusement to something closer to grief:

“...the moral of the story is a simple one. The world is in dreadful need of men who will assume the new leadership - who will have the courage of their own visions and who will recognise clearly that we are only at the beginning of the voyage, and have to learn an entirely new system of seamanship…the more I think of the problems of our lives, the more I am persuaded that we ought to choose Irony and Pity for our assessors and judges as the ancient Egyptians called upon the Goddess Isis and the Goddess Nephtys on behalf of their dead.”

The film adaptation of this book was not a history documentary, it was a narrative about God judging us for our failures (also the Marx brothers were pilgrims). Van Loon took us up the Tower of Experience so we could see the world, and he realized on the climb up that there are children in the tower, there are children in the tower, there are children in the tower, and they are dead already.

We have now read one hundred books for children, one hundred attempts to tell them about this stupid broken world and our stupid broken country and how maybe we ruined it and we're sorry and maybe they have a chance to save it but maybe they don't and I am sitting here in 2024 wondering if it’s beyond saving or even worth saving. I have mixed feelings about learning that this was apparently also an open question a hundred years ago.

But, of course, there aren’t one hundred Newbery medalists, there are one hundred and three. And we still have to read the last three.

Newburied is a series by Tony Ginocchio on the history of the Newbery Medal and a whole bunch of other stuff related to it. You can subscribe via Substack to get future installments sent to your inbox directly. The next installment will cover the 2022 medalist, The Last Cuentista by Donna Barba Higuera.

The Story Of Mankind has been reprinted multiple times, with additional chapters added by history professors to cover the post-WWI eras. The edition I got from my library was actually a 1984 printing that ran for almost 600 pages, but for the purpose of writing this essay I only read up through Van Loon’s original chapters.