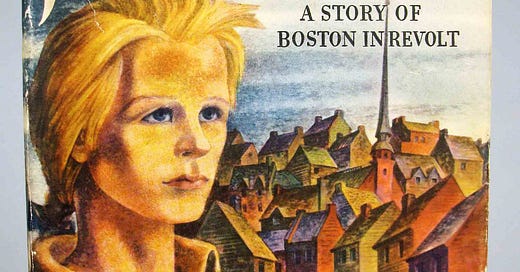

1944: JOHNNY TREMAIN by Esther Forbes

On rocky islands gulls woke. Time to be about their business.

Over the past several months, I've been up late rocking an infant to sleep while watching movies that an infant has no business watching. Scorsese's The Departed. Mann's Collateral. Cameron's Aliens and T2: Judgement Day. Fincher’s Fight Club. Schrader's The Card Counter. All awesome movies, all movies that my child is not allowed to actually watch while she's awake and old enough to be aware of what she’s watching.

This past week, the movie was Inglourious Basterds, which is Quentin Tarantino's best and most ambitious movie, better than every one of his other films including Pulp Fiction. Every performance is perfect, the pacing and building of tension are among the best I've seen in any film, and of course the revisionist take on World War II was great fun when I first saw the movie, and now feels…well, different.

What I'm trying to say is that I found a lot of badly needed comfort this past week, in 2022, watching a film where the Nazis lose, and lose horribly.

If you were on Jeopardy! and had to name some anti-Vietnam-War novels, two obvious picks would be Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five and Heller's Catch-22. Both of these novels are now regarded as satirical masterpieces, but they also both became hits very quickly after their initial publications, and were both favorites of 1960s college students nationwide, who laughed at the dark jokes in each novel and came to a better understanding of the absurdity of their time, a time when their government was sending people their age, chosen by lottery, to go off and die on the other side of the world, for what appeared to be very stupid reasons.

But even though both of these novels are considered obvious picks in the anti-Vietnam-War genre, neither of them are set in Vietnam, or set during the Vietnam War; both novels are set in Europe during the second World War, which is where and when Vonnegut and Heller themselves served (Slaughterhouse-Five is also set in, uh, several other places). The soldiers in the novels fight Nazis and fascists with the other Allied forces. No character goes to Vietnam or even mentions it in either novel. The war that Vonnegut and Heller describe is the one that we all know was fought for a great cause, and the soldiers serving believed in that cause and were welcomed home as heroes. This isn't Vietnam at all! This is a completely different thing!

But you're not an idiot - you're on Jeopardy!, after all - so you know that both of these men wrote these books, books that millions of people read and that are still in print today, because they had something to say about all wars, including the war that was happening right now. They had seen a war firsthand, and with that war ended and another very different one raging, they had something to say about how "different" wars can really be from each other, about whether wars can really ever “end".

You don't just write a book about a famous war and publish it during a different war, without saying something about the war you're currently in.

Johnny Tremain, title character of the 1944 Newbery medalist, begins his story as a fourteen-year-old boy in 1770s Boston, working in indentured servitude as a silversmith's apprentice. He also begins his story as a huge jagoff. He's great at his job and he knows it, he lords it over his fellow apprentices, and he's an unmanageable hothead, but he knows great things are coming his way; the best silversmith in the city, a guy named Paul Revere, has even offered to take Tremain under his wing on the side.

All of that goes to pot when a gruesome accident permanently disfigures Johnny's hand, immediately ending his career and leaving him on the hook to find another job quickly since he's still indentured. Johnny sinks into depression as he tries to find a way to feed himself and is met with a chorus of "AH JAWNY WHAT HAPPENED TA YA HAND S'WICKED MESSED UP GO PATS". The only gig he's able to find is riding across Massachusetts to deliver copies of the Boston Observer, a newspaper that happens to be publishing increasingly inflammatory essays by men like Revere, John Hancock, and Boston's biggest rabble-rouser, Sam Adams. As he spends more time with the disgruntled Yankees, Johnny eventually finds himself witnessing and participating in some of the key inciting incidents of the Revolutionary War. He gets recruited to jump onto a British ship and dump their tea shipment into the Boston Harbor, all while disguised as, and talking like, an "Indian" (AH JAWNY NO DON'T DO IT THEYA GONNA CANCEL YA WICKED HAAAAAHD GOOD WILL HUNTING). He ingratiates himself to the redcoats in the taverns and passes his intelligence on to the Sons of Liberty. And he eventually helps Paul Revere spread the word of the incoming British attack at Lexington and Concord. The novel ends right after that battle, with the revolution now underway and Johnny feeling confident that the rebels will prevail, thanks to the righteousness of their cause.

I didn't read Johnny Tremain as a boy, but I expect that if I did, I would have enjoyed it. Johnny is a great character who goes on a moving journey as he learns to stop being so full of himself and work with others to support something bigger. The story keeps moving, with all sorts of cool spycraft and period details. Tremain is certainly one of the pillars of the Newbery roster: the book has never been out of print since its original publication almost eighty years ago, and remains a staple of middle school reading lists today. It is also, famously, Bart Simpson's favorite book.

Esther Forbes had written several historical novels earlier in her career, and the year before Johnny Tremain came out, she won a Pulitzer for writing a nonfiction biography of Paul Revere. Forbes' historical expertise is obvious: the best parts of the novel are her descriptions of a cramped and noisy Boston bustling and eventually buckling as the calls for revolution get louder, of how the different social classes scrape against each other and eventually against the redcoat army, of how the rumors of war fly through the city as people start arguing over what it is they really want to fight for. Both the Revere biography and Tremain, Forbes' most decorated works, came out in the mid-1940s, when America was years into the second World War, still watching their children fight and die over in Europe and the Pacific. Forbes started writing Tremain the day after Pearl Harbor was attacked, the day that the United States entered the war.

You don't just write a book about a famous war and publish it during a different war, without saying something about the war you're currently in.

Johnny Tremain is a book for fifth graders, so it isn't really trying to be subtle. It's very obvious which chapter is the Big Important Chapter, and that's Chapter VIII, "A World To Come", and specifically the Big Important Scene is a secret meeting of the rebels right before the war erupts. Sam Adams is about to go off to the Continental Congress and agitate for war, which sets off a debate on what it is the rebels are actually fighting for. As Adams says, "it's time to free Boston from these infernal redcoats," but as another obscure revolutionary named James Otis suggests, maybe that's not good enough by itself:

"That’s not enough reason for going into a war. Did any occupied city ever have better treatment than we’ve had from the British? Has one rebellious newspaper been stopped—one treasonable speech? Where are the firing squads, the jails jammed with political prisoners? What about the gallows for you, Sam Adams, and you, John Hancock? It has never been set up. I hate those infernal British troops spread all over my town as much as you do. Can’t move these days without stepping on a soldier. But we are not going off into a civil war merely to get them out of Boston. Why are we going to fight? Why, why?’"

"The British aren't actually that bad" was not a popular take at Sons of Liberty meetings, but Otis' point is that this war should be about something bigger. It shouldn't just be about tea taxes, and it shouldn't just be about the rights of the colonists alone:

"...for even as we shoot down the British soldiers we are fighting for rights such as they will be enjoying a hundred years from now. There shall be no more tyranny. A handful of men cannot seize power over thousands. A man shall choose who it is shall rule over him. The peasants of France, the serfs of Russia. Hardly more than animals now. But because we fight, they shall see freedom like a new sun rising in the west."

The war, to Otis, is to show the world that men (it was only men at the time, and oops, as it turns out, it's still only men now) could rule themselves and not live under the divine right of kings. Put another way:

"It is all so much simpler than you think. We give all we have, lives, property, safety, skills . . . we fight, we die, for a simple thing. Only that a man can stand up."

"That a man can stand up", as a summary of the revolutionary project, is repeated throughout Tremain, including in the final lines. This theme has never died in American literature: seventy-three years after Tremain, George Saunders would win the Man Booker Prize for his stunning novel Lincoln In The Bardo, in which Abraham Lincoln, grieving his dead son and the grueling civil war, forges ahead and keeps fighting to hold the Union together, to prove one very important thing to the world:

"Across the sea fat kings watched and were gleeful, that something begun so well had now gone off the rails (as down South similar kings watched), and if it went off the rails, so went the whole kit, forever, and if someone ever thought to start it up again, well, it would be said (and said truly): The rabble cannot manage itself.

Well, the rabble could. The rabble would."

As cynical as I can get about how well America has lived up to its revolutionary promise and trusted the rabble's ability to lead, as hard as it is to look at who actually can and can't "stand up" in America today, it's still very moving to read words like these, about the ideal that people deserve to rule themselves. I can imagine it would be moving to read those words as a child. I cannot imagine what it would be like to read those words while my hypothetical brother was off fighting Nazis in Europe, when people I knew had joined together to fight in another war, this time to keep fascist darkness from swallowing the earth whole.

I do, however, know what it feels like to read it while you wonder if that war against fascism and authoritarianism, a war fought so people could stand up, so the world could be inspired and believe that people really could rule themselves, ever really “ended”, or just curdled into something thick and slow and heavy.

In the world of Johnny Tremain, the Revolutionary War was fought "so a man can stand up", or, to put that in Forbes' less abstract terms, so that "a handful of men cannot seize power over thousands. A man shall choose who it is shall rule over him". That was the war, and the cause, that Forbes wrote about, in order to tell young readers that this war, in a way, was still being fought today, that this World War had the same enduring cause, and that this cause was still righteous. There's a reason that the Big Important Chapter isn't set at a battle, but at an argument over what the war is really about. Forbes wanted to teach her readers that America always fights so that the few will not rule over the many.

Writers like Vonnegut and Heller wrote about the war that Forbes lived through, in order to tell their readers something about yet another war: that as righteous as our causes might be, our own ability to liberate the many from rule by the few was perhaps not quite as rock-solid as we had once assumed, that perhaps we maybe hadn’t resolved all of the problems tha came with putting a country together, that perhaps we still had our own problems with the few ruling the many here at home, that perhaps the world that America had built around these ideals was starting to rot. Part of the reason Vonnegut and Heller wrote like this was because they were witnessing a war that looked very different from the second World War, and also, they had one big piece of information that Forbes didn't: Forbes had written and published Tremain, and had received her Newbery medal, all before the end of the second World War, before her good brave country fighting so that a man could stand up had ended that war by leveling two Japanese cities and killing hundreds of thousands of civilians, using tools of previously unimaginable devastation, tools which still exist today and which could still stop everyone from standing up ever again.

Today, I don't have anything new to say about whether the many in America are actually ruling themselves, or whether the few are still crushing them underfoot, about whether we've ever actually built anything even close to our fancy-sounding ideals about self-rule and democracy. I think we're all aware of how well that's all working out. It's tempting to look at everything that is happening right now and sarcastically ask how far we've really come from the first war fought "so that a man can stand up". But that assumes that this war ended in the first place, that it's not still happening right now, that it doesn’t still have to keep being fought, that we're not still seen as enemies and targets by a handful of men who have seized power over millions. The better question will always be: how is the first war fought "so that a man can stand up" going to end?

Newburied is a series by Tony Ginocchio on the history of the Newbery Medal and a whole bunch of other stuff related to it. You can subscribe via Substack to get future installments sent to your inbox directly. The next installment will cover the 2008 medalist, Good Masters! Sweet Ladies!: Voices From A Medieval Village by Laura Amy Schlitz.