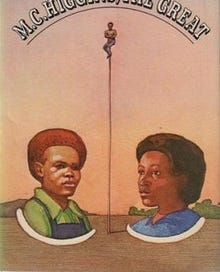

1975: M.C. HIGGINS, THE GREAT by Virginia Hamilton

Mayo Cornelius Higgins raised his arms high to the sky and spread them wide.

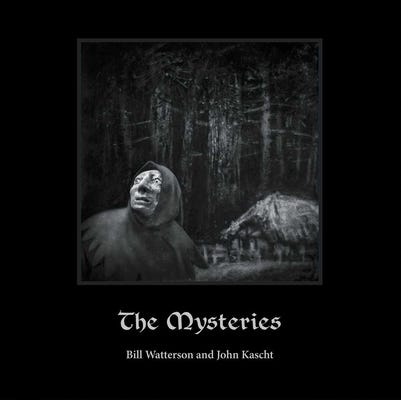

A few months ago we talked about Bill Watterson, the cartoonist who created Calvin and Hobbes, and I mentioned in passing that in late 2023, the famously media-shy and extremely deliberate author had finally released his first major post-Calvin work. He co-authored it with John Kascht, and it’s called The Mysteries.

That doesn’t exactly look like a Calvin and Hobbes strip. It doesn’t feel like one, either; the author who shaped my childhood sense of humor came back with what he describes as “a fable for grown-ups”, something extremely ominous, something that feels like a warning. What makes The Mysteries even more unsettling is how sparse it is: the full text - credited entirely to Watterson - takes about two minutes to read, with one sentence on each page. The fable goes like this: there once was a kingdom, surrounded by mysteries that they didn’t understand, mysteries that frightened, hurt, and killed them. The king sent knights to investigate what the Mysteries were, and after many years, the people of the kingdom were relieved to learn that the Mysteries weren’t so complex after all. People stopped being afraid of the Mysteries, and eventually lived large without them.

Through some context clues in the illustrations, it becomes pretty clear that “the Mysteries” is referring to something like “a primitive fear of and general deference to the unknowable in nature”. As the kingdom slowly comes to understand the Mysteries, it builds up into a modern city. One illustration has an onlooker laughing at an old painting of the Mysteries, relieved that society is no longer afraid of anything so foolish. The painting depicts what appears to be one of the horsemen of the apocalypse, although it’s not clear whether the man is laughing at the now-obsolete idea of famine, plague, war, or death.

The kingdom is no longer scared of the Mysteries, and we never really learn how the Mysteries feel about that, but we do notice some other strange things start to happen: the ground is starting to shake, the sky is starting to turn a weird color, animals are migrating or outright disappearing. As Watterson puts it, “Rather late,/the people grew alarmed.” And immediately after that line, this is how the story ends:

“Time moved on.

Centuries passed.

Eons passed.

The universe continued as usual.

And the Mysteries lived happily ever after.”

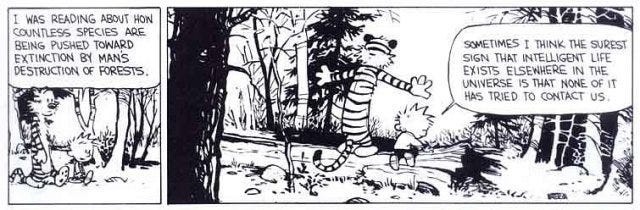

So I got the book as a gift three months ago and I’m still thinking about it. It’s pretty chilling. I’m not sure if Watterson is some sort of Luddite - I doubt that’s the case, but I wouldn’t exactly be shocked if it were true - but you can find an existential and environmental message here that follows a line drawn from Calvin and Hobbes. The latter one is a little easier to see in both works. Take a look at this strip:

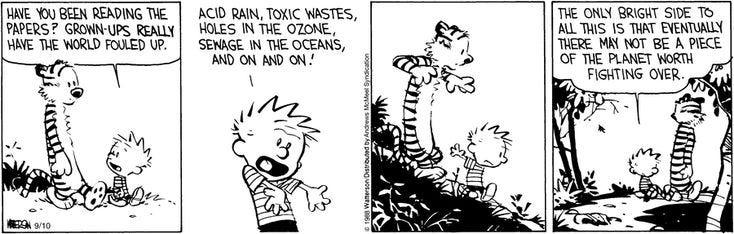

Or this one:

Calvin was always worried about the grown-ups, who supposedly knew better than he did, destroying his planet. But of course, they weren’t destroying the planet, and we’re not destroying the planet, either. The planet is going to be just fine without us. We’re the ones who will end up destroyed, and the Mysteries will live happily ever after. Read in this light, The Mysteries that we were no longer afraid of were the elements and the Earth that we couldn’t control. But now we can, and it’s possible that the control we wanted so badly is going to end up killing us all. But it’s possible that this is more than an environmental story, as Rivka Galchen wrote in her review of the book for the New Yorker:

“Mastering the secrets of the mysteries brought about a lot of technological marvels, and made the people less fearful. Or you might say insufficiently fearful: the woods are cut down, the air becomes acrid, and eventually the land looks prehistoric, desiccated, hostile to life. In one read, “The Mysteries” is a nephew of Dr. Seuss’s “The Lorax.” It’s also kin to the ancient story of Prometheus, a myth we now associate with technological advancements. Prometheus took pity on the struggling humans, and stole fire from the gods to share it with them. And how has that magnificently useful fire gone for the humans? Pretty well by some measures, pretty catastrophically by others. If only humans heeded the warnings within mysteries as well as they followed the blueprints for making Teflon pans and missiles…Enchantment! If disenchantment is the loss of myth and illusion in our lives, then what is the chant that calls those essentials back? An ongoing enchantment is at the heart of “Calvin and Hobbes.” It’s at the heart of “Don Quixote” and “Peter Pan,” too. These are stories about difficult and not infrequently destructive characters who are lost in their own worlds. At the same time, these characters embody most of what is good: the gifts of play, of the inner life, of imagining something other than what is there. If “The Mysteries” is a fable, then its moral might be that, when we believe we’ve understood the mysteries, we are misunderstanding; when we think we’ve solved them and have moved on, that error can be our dissolution.”

Maybe we didn’t respect our home enough, maybe we tried to develop too many things too quickly, maybe we don’t know how to practice wonder and awe anymore, maybe we didn’t think about the future, maybe we need to be scared of things a little bit more…I don’t know. But Watterson’s story is that we missed some signpost somewhere, and when you think about it, it really doesn’t matter, because the Mysteries are going to be just fine without us.

M.C. Higgins The Great, the first Newbery medalist by an African-American author and you would have thought that would have definitely happened before 1975 but here we are, is very weird. There are a lot of individual parts to the novel, and each individual part is weird, and they fit together in a weird way. The simplest way to understand the novel is as a character study of Mayo Cornelius Higgins, a teen living among Appalachian hill people on a mountain in Kentucky, currently being strip-mined to shit by some faraway corporation. We follow M.C. as he navigates his strained relationship with his father and crushes on a girl passing through town, and tries to flag down a visiting A&R guy to get his mom a singing contract, and practices his favorite hobby in his spare time: sitting on top of a forty-foot metal pole. I told you it was weird.

The conflict that keeps reappearing throughout the plot is this: the mining has left a large hazardous pile of “spoil” - strip mine tailings, basically a giant mass of rock, dirt, and hazardous chemicals - uphill from the Higgins house, and M.C. is constantly fretting over whether it’s going to eventually collapse and destroy his home. Because of this, M.C. wants to leave, he wants to get the hell out of Kentucky, hopefully move to Nashville or New York if his mother lands a recording contract, because that spoil is literally hanging over his head and he’s scared of what’s going to happen if no steps are taken to “slow the ruin down”. But that’s not the conflict, that’s what M.C. worries about.

The conflict is that while M.C. wants to get as far away as he can from the approaching spoil, M.C.’s father - referred to only as “Jones” by M.C., every other character, and the narrator - has no desire to leave at all. Jones’ entire family, going back generations, is buried behind his home - the junk in the backyard, including M.C.’s climbing pole, all serve as unofficial tombstones - and it’s the only place where he knows how to live. Which leads to multiple internal monologues from M.C. like this:

“How am I going to get him to leave? Why come he can’t see that spoil is going to fall, when even a dude out of nowhere can see it? When the kids can. They don’t say nothing ‘cause it scares them. But they can see it. He must see it. So what does he think he’s doing?”

There’s other stuff that happens in the novel, too, but all of it orbits around this tension: the teenager knows that his world is dying and wants to do anything to get the hell out of there or at least slow the ruin down, and the elder doesn’t understand any world outside of the one that’s going to die with him on it. He just wants to go to work and come home and make potato soup for his family. As the novel continues and as it becomes clear that Jones is well aware of the risk of staying where he is, we realize that this isn’t a story about M.C. trying to shake his dad out of his naivete, but rather a story about a dad who is trying not to think about how horrifying it is to be trapped inside a collapsing world, trying to just distract himself with anything else so that he can at least function as a person and earn money at his job and occasionally be around to spend time with his kids. A real light bedtime read for a dad in a dying world.

In the final scene of the novel, M.C. has come to terms with the fact that he’s never leaving Appalachia. Multiple rays of hope for him - a visiting stranger, a possible record deal for his mother - have all fallen through, and, almost on a whim, he and his younger siblings begin to dig up some soil and put together a crude barricade between the spoil pile and the house. And then Jones comes out and sees them:

“Jones came closer to them to watch…When it came to him what M.C. was trying to do, he gazed up at the top of Sarah’s [Mountain]. He could see the dark and giant heap rising out of mist like a festering boil. He looked down at the bent, straining backs of the children, astonishment creeping into his eyes. He shook his head at them, but he continued to stand there, silently watching M.C.’s arm and the bit of dirt and rock loosened with each downward stab. Jones stood there a long while before he turns and went to the front porch. He kneeled at the side of the porch and crawled halfway under on his belly. His legs stretched and strained; and when he came out again, he was dragging a piece of shovel.”

I’m not really sure how the Newbery committee picked this book for the medal, or why it’s one of only two books in history to win both the Newbery and the National Book Award (the other is Holes). Maybe it was just because the image here at the end was unlike anything they had seen before, communicated something dark and ominous and desperate that nobody had found in any of the previous medal-winning novels: children, up to their knees in dirt, knowing that the Earth will continue to suffer long after they’re gone, grabbing pieces of metal and rock, recruiting their dad, and all making frantic piles to slow the ruin down.

Newburied is a series by Tony Ginocchio on the history of the Newbery Medal and a whole bunch of other stuff related to it. You can subscribe via Substack to get future installments sent to your inbox directly. The next installment will cover the 1938 medalist, The White Stag by Kate Seredy.