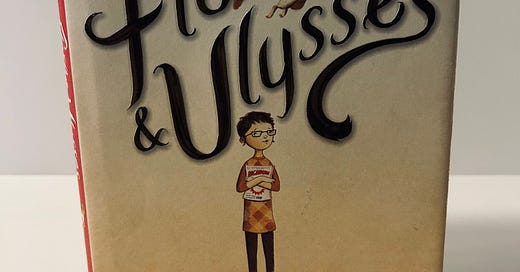

2014: FLORA AND ULYSSES: THE ILLUMINATED ADVENTURES by Kate DiCamillo with illustrations by K.G. Campbell

IN THE TICKHAM KITCHEN, LATE ON A SUMMER AFTERNOON…

“I set out to tell the story of a vacuum cleaner and a squirrel. I ended up writing a book about superheroes, cynics, poetry, love, giant donuts, little shepherdess lamps, and how we are all working to find our way home. Seal blubber!”

-a thing Kate DiCamillo actually writes on the back jacket copy of this book

Dear Ms. DiCamillo:

Okay. We're going to try this again. I know things got a little tense during our last correspondence, but I'm going to make a good faith effort to engage with you on your second Newbery medalist, Flora And Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures. I will start with some compliments: my oldest daughter, who is now five years old, enjoys your Mercy Watson series for young readers a great deal. So that's something. You also make a reference to Pascal's Wager in your book and get it right when many others get it wrong: the Wager is not to believe in the transcendental so you can go to heaven after you die, it's to believe in the transcendental so your life can have meaning before you die. So good work on that.

I am trying to act in good faith here, I really am. But I am really struggling with your second Newbery medalist, Flora And Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures. I don’t understand the characterization of Flora as a “cynic”, which doesn’t seem to align with her diet of superhero comics and her immediate belief in the supernatural power of the squirrel Ulysses. I also - and this goes without saying - have no idea how Ulysses gained the power of flight or the capacity to write in English using a typewriter like that damn golden retriever in Watchers, because the only information given in the book is that he was sucked up by an industrial vacuum cleaner and gained his powers that way. But even putting aside the murky origin of the superpowers, the superpowers don’t mean anything. Ulysses does nothing with them, he doesn’t help anyone, he doesn’t even help himself and has to be rescued by the very un-super Flora and her (sighs heavily) ten-year-old friend who is pretending to be blind because he’s mad at his stepdad for some reason, and specifically he has to be reduced from Flora’s mother, who is a romance novelist that is planning to murder the squirrel with a shovel for no real reason other than “she doesn’t like that her daughter is friends with a squirrel”, and looking back at this paragraph, I don’t even fully understand what I’m writing anymore. So please, Ms. DiCamillo, I’m begging you, can we please just start by having you tell me what happens in Flora And Ulysses? If a middle grade reader came to you and asked you about it, how would you describe the plot of the novel to them?

Thank you again for your time.

Tony Ginocchio

Young Master Ginocchio:

The plot of the novel? What of the TRUTH of the novel? Nay, what of the very LIGHT of the novel? What of the LIGHT that we writers provide to guide our readers through the darkness of their story-less, miserable lives? For again, dear reader, we are in the trade, not of story and empty show, but of light and truth! And it is the light and truth of heroism and love and poetry that I have brought to you and my other readers!

I remain, as always, your obedient servant &c.,

K. DiC.

Dear Ms. DiCamillo:

Do you think this is good? Do you think this is good writing? Do you think it’s good writing when you name characters things like Tootie Tickham or Alfred T. Slipper and then continuously refer to them by their full names throughout the novel? Do you think this is good writing when one of the characters says “Your father is so far off in left field that he wouldn’t recognize love if it stood up in his soup and sang”? Why is it soup again? Why is it always soup with you?

I really want to know this, I’m asking in earnest. Why do you think your writing is good? Why does the ALA think it’s good and not unbelievably overwrought and pretentious? The reason I’m asking the question this way is because you actually ask it of one of your characters. Flora’s mother is a romance novelist, and in one scene, the precocious fake-blind stepdad-hating best friend William Spiver is giving her advice on how to write her next novel:

“‘Yes, exactly,’ said William Spiver. ‘More poetic. ‘Eons’ sounds too geological. There’s nothing romantic about geology, I assure you.

‘Okay, okay,’ said Flora’s mother. ‘Right. What’s next, William?’

‘Actually,’ said William Spiver, ‘if you don’t mind, I would prefer to be called William Spiver.’

‘Of course,’ said Flora’s mother. ‘I’m sorry. What’s next, William Spiver?’

‘Let me see,’ said William Spiver. ‘I suppose Frederico would say, ‘And I have dreamed of you, Angelique. My darling! I must tell you that they were dreams so vivid and beautiful that I am loath to wake to reality.’

‘Ooooh, that’s good. Hold on a sec.’

The typewriter keys came to clacking life. The carriage return dinged.

‘Do you think that’s good?’ Flora whispered to Ulysses. ‘Do you think that’s good writing?’

Ulysses shook his head. His whiskers brushed against her cheek.

‘I don’t think so, either,’ she said.

Actually, she thought it was terrible. It was sickly sweet nonsense. There was a word for that. What was it?

Treacle. That was it.”

What is this! Why would you introduce a treacly writer as a major character and have treacliness be worthy of criticism in a Kate DiCamillo novel! Aren’t you asking for trouble there? Why the hell did you not only refer to William Spiver by his full name throughout, but actually have William Spiver interrupt the conversation partway through to reinforce that, yes, in fact, we will be referring to him by his full first and last name for the rest of the novel? Do you have to hit a word count on these things?

I’m sorry, I’m just frustrated, because there is nothing here. This ended up as less than the sum of its parts. One part is a comic book superhero story, illustrated intermittently throughout the novel in comic panels, but the superpowers don’t make any sense and don’t mean anything. But also it’s a story about divorce which seems completely detached from the superhero story, and then there’s a separate divorce elsewhere in the story which barely seems connected to anything else at all. You said this is a story about cynics but Flora isn’t cynical, she just gets into arguments with her mother. When presented with a squirrel with superhuman powers, she embraces him right away - she even gives him CPR at the beginning of the novel - while a different, far more cynical character dismisses the squirrel as ridiculous. You say it’s a book about giant donuts, the giant donut is in one scene. The little shepherdess lamp - and you say this is also a book about that - makes no sense at all. It doesn’t make sense why Flora’s mother loves it so much, it doesn’t make sense as a plot point. You are just jamming funny names, non-sequiturs, and clashing genres into the blender, and the ALA is just riding your dick all over again. I’m so sick of this. I am so sick of this.

Okay, I’m done. It’s out of my system now. I can move on.

Thank you again for your time.

Tony Ginocchio

Young Master Ginocchio:

Seal blubber, I say to you, sir. Seal blubber.

I remain, as always, your obedient servant &c.,

K. DiC.

Dear Ms. DiCamillo:

Okay, come on, what the hell is seal blubber! Why is that a refrain throughout the book! Here’s the first mention of it:

“[One of Flora’s favorite books] Terrible Things Can Happen To You! had done an extensive piece on what to do if you were stranded at the South Pole. Their advice could be summed up in three simple words: ‘Eat seal blubber.’ It was astonishing, really, what people could live through. Flora felt cheered up all of a sudden, just thinking about eating seal blubber and doing impossible things, surviving when the odds were against her and her squirrel.”

Okay, so what I think I’m supposed to take away from this is that Flora says that to herself to remind her that she could survive when things seem difficult and bleak. I assume that’s what it means. Now, when you put it in the jacket copy after describing what the book was about, it didn’t make any sense, not with that connotation or with any other connotation, and then there are plenty of passages like this one, where Flora is looking at a painting of a giant squid:

“‘The giant squid is the loneliest creature in all existence,’ said Flora out loud. And then, to keep things grounded and in perspective, she muttered, ‘Seal blubber.’ And then she whispered, ‘Do not hope; instead, observe.’ She kept her hand on the squirrel.”

So, “seal blubber” appears to mean nothing there, and the other refrain is from a different book she reads and repeats to herself all of the time, and while none of those refrains seem to really connect to each other at all or contribute to the plot or have any real resemblance to the putative themes of the novel, it just seems like Flora’s main character trait is that “she repeats a lot of things over and over, much like you repeat the full first and last names of most of your characters across all of your books.” Which is not a good character trait! It would be better if she repeated one thing, not like eight different things, because then you could build a more precisely defined character around that one phrase. But if you just have a character who rotates through multiple catchphrases, that just, again, feels like you’re hitting a word count! I believe you when you said you set out to write a different novel, because I think you kept setting out to write different novels and then jammed them all in to this piece of crap!

How can a squirrel gain superpowers from getting sucked into a vacuum cleaner? Is the vacuum cleaner running on plutonium? Why do Flora’s parents have to be divorced? Why is Flora reading survivalist books? Why does any of this belong with any of the rest of it? What are you? What do you do?

Thank you again for your time.

Tony Ginocchio

Young Master Ginocchio:

You scoundrel. I have convened the Council of Six - which is me, Matt de la Pena, Donna Barba Higuera, Blue Balliet, John Green, and Karen Cushman - and we have condemned you to death by firing squad. You are to report to Independence Hall in Philadelphia at dawn tomorrow. I regret that it has come to this, but we will not allow an enemy of the light such as yourself to continue spreading this filth.

I remain, as always, your obedient servant &c.,

K. DiC.

Dear Ms. DiCamillo:

Again with this Council of Six bullshit?!?!

Newburied is a series by Tony Ginocchio on the history of the Newbery Medal and a whole bunch of other stuff related to it. You can subscribe via Substack to get future installments sent to your inbox directly. The next installment will cover the 1996 medalist, The Midwife’s Apprentice by Karen Cushman.