In spring of 2022, I was looking for a new project. I thought I had finished with G.O.T.H.S., I had been working on a short book of essays about Catholicism but it wasn’t going anywhere, I wasn’t ready to start working on any fiction, but I was deleting my Twitter account and looking for another way to waste my time, and I was looking to write about something completely unrelated to the stuff I had written about for the past two years. And one thing I loved talking about was children’s literature, and I batted around a few ideas on topics in children’s literature I could write about. One idea that I almost moved forward with was a short book of essays about the novels of Daniel Pinkwater, my favorite children’s author of all time, who wrote many brilliant works that I could dig into deeply to help explain why I saw the world the way I did, and what I wanted to teach my daughters. But that idea ended up getting scrapped, and I wrote about my obsession with the Newbery medal instead, and it’s been a wonderful project so far, one that I love sharing with you and one that is always a tremendous amount of fun to work on. However.

Of the one hundred and three Newbery medal winners in history, two do not have circulating copies available anywhere within the Chicago Public Library system. One of them, Smoky The Cowhorse, is old enough to be in the public domain and easily available as an ebook so you can read it today if you want to, but you should not want to, because it is terrible. The other book is 1940 nonfiction medalist Daniel Boone, which is out of print, not old enough to be in the public domain, and difficult to find on the secondary market. I can find a copy for about $42 in “acceptable” condition, but I was not able to spend that, having already spent that exact amount of money on a different out-of-print book for the other newsletter.

In 2010, the American Library Association reported CPL’s total collection at 5,721,334 volumes; one assumes that the collection has grown in the past fourteen years (like they probably added all of the Colleen Hoover books or whatever). Only one of those volumes is a copy of Daniel Boone, kept on the left-hand side of the bottom shelf of non-circulating Newbery medalists, filed in chronological order near the entrance of the Thomas Hughes Children’s Library, located on the second floor of the Harold Washington Library Center, which is the Chicago Public Library’s main branch building, located downtown at State and Van Buren. The volume is only available for in-library use and is not able to be checked out.

Complicating matters further: if you are an adult and do not have a child accompanying you, you can’t just sit in the middle of the Thomas Hughes Children’s Library by yourself, a rule WHICH THE SECURITY GUARD TAKES VERY SERIOUSLY. Thankfully, you can just take the book to a reading stall on another floor without having to check it out.

So, one afternoon, my parents had planned an exciting day downtown with my five-year-old daughter, seeing a children’s concert at Orchestra Hall at Chicago Symphony Center1. The concert was forty-five minutes long, which meant I could drop my daughter off with my parents, run three blocks over to the library, find the book I needed, and read as much of it as I could before running the three blocks back to pick up my daughter at the end of the concert. And because Daniel Boone is 94 pages including some full-page illustrations, “as much of it as I could” ended up being “the whole thing if I kind of skim in places”, which is exactly how that shit went down.

Now, I have not retained a great deal of the book - I’m vaguely aware that Daniel Boone is the guy who invented Kentucky or something - but I took a couple of photos of various pages, feeling like some sort of spy who had gotten his hands on some incredibly rare documents, which was basically an accurate description of the situation. As Daugherty put it in the intro, addressing Boone directly:

“You kept your rendezvous with destiny. When history called for men of action you were there. And so your name still echoes in the mountain passes and is a whisper and a heart-beat along the old trail. Your image is a living flame, ever young in the heart and bright dream of America marching on.”

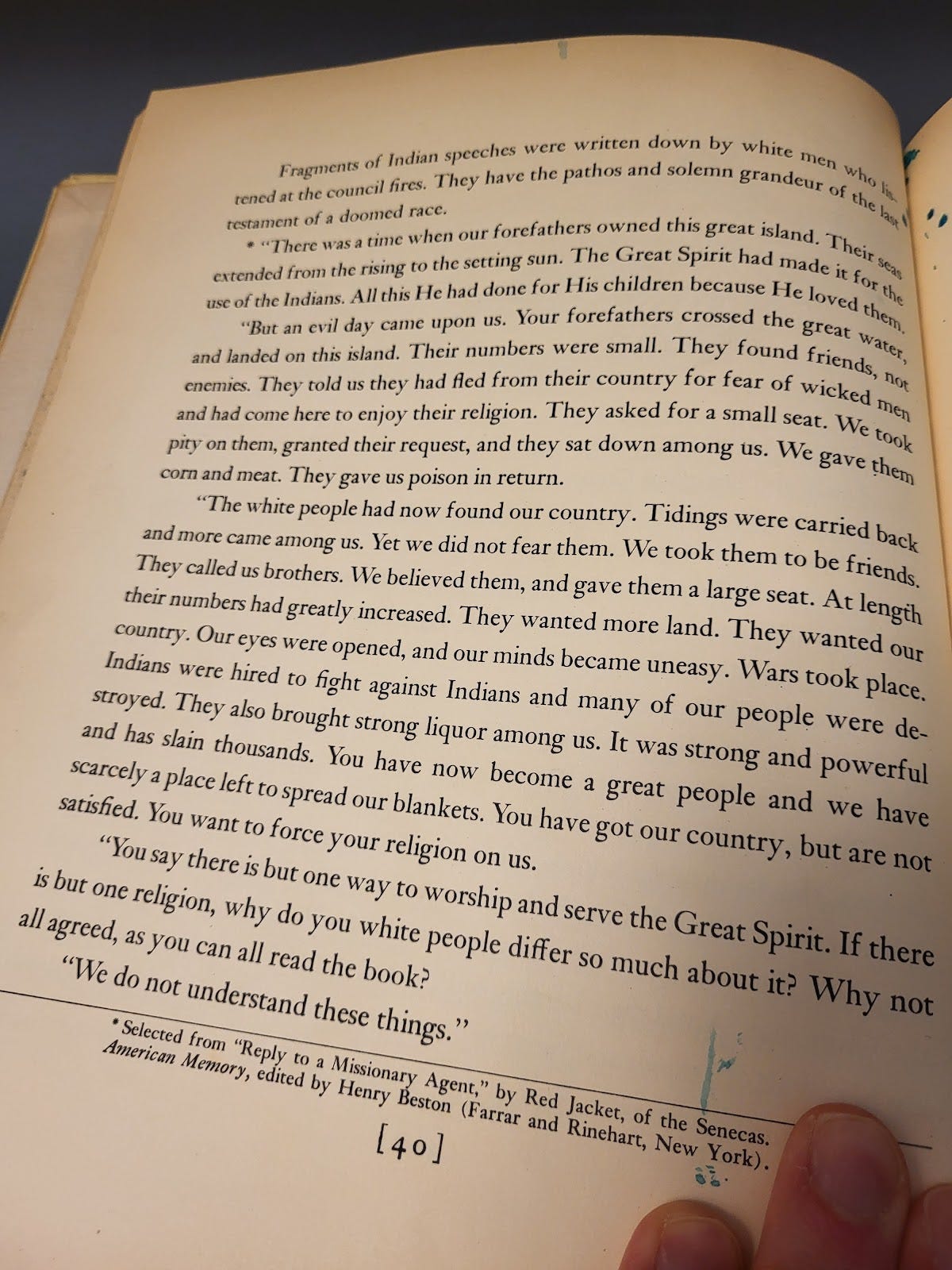

Stirring words addressed to a man whose most famous biography for children is permanently out of print and can only be read through dark library sorcery. Look, the book is fine. There’s actually a sort-of moving passage where Daugherty transcribes some letters from indigenous Americans that offhandedly reveal how brutally they were treated my colonial Americans, and another moving passage about the tragedies of industrialization sweeping the country as the moneyed North pressed men into wage-slavery and financialization, and the extractive South pressed men into a more literal kind of slavery. I liked those passages and took photos of them if you care to read:

I’ve said about all I have to say on Daniel Boone. There’s another children’s book that only has one copy among the over five million volumes in the CPL system, although it happens to be a circulating copy. But it’s tragic that there’s only one of them, because it happens to be the single greatest children’s novel ever written - better than all of the Newbery medalists - and I’m going to just ignore Daniel Boone for the rest of the essay and give the space to this great book instead: The Snarkout Boys And The Avocado Of Death, by - you guessed it - Daniel Manus Pinkwater.

If you ever look at my profile pic on Substack or if you ever looked at my old profile picture when I had a Twitter account, you'd notice that it wasn't a headshot of me, it was a crop of the above book cover, a drawing of the bespectacled teen Walter Galt hypnotized by the sinister wired-up Avocado of Death. That's how important this book is. My online identity is one I want you to associate with this book. I read it to both of my newborn daughters when I was up late with each of them, because I wanted them to basically imprint upon the book as infants. As with all great Daniel Pinkwater novels - Borgel, The Worms Of Kukumlima, Alan Mendelsohn The Boy From Mars - Avocado is a story about friendship between people who find it hard to make friends. It's about that moment when things turn and you realize that this person you've spent so much time with is someone you like, and is someone who likes you too, and you like spending time with each other, and this way of spending time became more special because now it is a friendship. And then, like all great Pinkwater novels, including the ones I listed above, it takes an unexpected hard left turn about forty percent in and becomes absurdist slapstick sci-fi. That is how you write a damn book.

In Avocado, nerdy protagonist Walter Galt is miserable as a freshman at the bottom of the social order at Genghis Khan High School. But he connects with his classmate, the portly and caustic Winston Bongo, who introduces him to “Snarking Out” - that is, sneaking out of your home in the middle of the night to catch the bus to a double screening at the all-night Snark Theater, which has a new double bill every twenty-four hours. They make friends with other regulars at the movie theater, and then they eventually get entangled in a caper to stop a criminal mastermind and his evil mind-controlling avocado that may be the key to galactic stability.

Had I actually written that imagined book of Essays On Daniel Pinkwater, Avocado would have been the topic of at least three separate essays. For one thing, the setting of the fictional city of Baconburg is a stand-in for Chicago's Old Town neighborhood. The Snark Theater is, in turn, a stand in for Piper's Alley at North and Wells, now the home of Second City but also a haven for independent film back in the day. Old Town, in the early twentieth century, was the home of Chicago's anarchist movement, leftist thinkers like Emma Goldman, and radical hangouts like the Dill Pickle Club, home to freewheeling leftist speechmaking. The latter is reflected in the novel when Walter gives an extemporaneous speech in a public park during a Snarkout, and while he starts with just complaining about his lousy school, you can hear the radical rebellion start to creep in to his words:

“I’m not getting educated, and nobody in my school is getting educated…What’s wrong with me is that my school is part garbage can and part loony bin. My biology teacher is about a hundred years old and talks to things that can’t answer back. My English teacher is a full-time professional Jew-hater. My math teacher is always falling sleep in the classroom. My history teacher talks about nothing but his personal problems, and the gym teacher is some kind of homicidal maniac! That’s what’s wrong with me! I’m growing up ignorant, and I don’t particularly want to!”

The story with that classic Pinkwaterian left turn is there. The Chicago history is there. The teenage frustration that leads directly to anarchist politics, AS IT SHOULD, is there. But what gets me the most is the double bill of the Snark Theater itself. When Walter and Winston go to the midnight double feature, they sit and they watch what's in front of them. Sometimes they hit the jackpot and they get to see a string of Laurel and Hardy shorts. And sometimes they watch total garbage, and sometimes they watch weird art films from sixty years ago and sometimes they watch new stuff, and sometimes they watch old vampire movies. But they watch it all, because it's there, and someone made it, and they want to discover it, late at night, half asleep, and then they walk into the all-night diners and talk to the people they find there and order the baked potatoes because that's the special and they want to eat what's the special at this diner.

That’s what I love, that’s what I still love today, that’s the love I hope to pass on to my daughters. This discovery, this all-consuming curiosity, this desire to take in as much as possible of what others have made in an attempt to turn the human experience into something more than a gray bowl of slop. To sit myself down and see what others have done to further our collective understanding of what it means to be a human being. To see the attempts that have been successful beyond imagining, and to see the ones that have been hilarious failures, and to walk away from each of them a richer, more complete person, one with a greater understanding of how I can take the swirling roaring noise into my brain and turn it into words or music or art that will someday forge a connection with another human being who has another swirling roaring noise in their brain, so that someday we can both realize that this person you've spent so much time with is someone you like, and it someone who likes you too, and you like spending time with each other, and this way of spending time became more special because now it is a friendship. I hope I never lose that all-consuming curiosity. Even if it means some late nights. Even if it means witnessing some spectacular failures. Even if it means reading through a list of one hundred and three books and making the trek downtown to find that last one.

Newburied is a series by Tony Ginocchio on the history of the Newbery Medal and a whole bunch of other stuff related to it. You can subscribe via Substack to get future installments sent to your inbox directly. The next installment will cover the 2014 medalist, Flora And Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures by Kate DiCamillo.

Please refer to it by its full name.