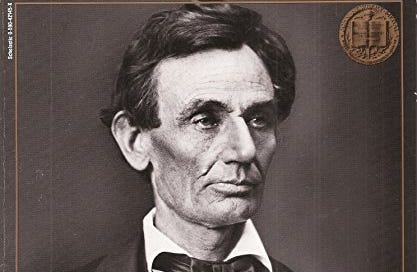

1988: LINCOLN: A PHOTOBIOGRAPHY by Russell Freedman

Abraham Lincoln wasn't the sort of man who could lose himself in a crowd.

In an episode of The Americans, a 2010s drama series about Soviet spies living undercover in 1980s Maryland, the spies are gearing up for a trip to Illinois. Their KGB handler muses to himself "Illinois, the land of Lincoln…to think, this country once had a Lincoln." He sighs, "and now they have a Reagan," and it's all you can do not to yell out "buddy you have no idea where this is all heading".

"We deserve this, and to be honest, we probably deserved worse" strikes me as a politically unwise thing to say after a history-defining mass casualty event. We just had a history-defining mass casualty event (we're kind of still having it), and the message from almost every world leader has not been "wow this has really hurt us because we structured our society in a way that left us very vulnerable to this sort of thing and we need to do better in the future"; the only figure on the world stage to say anything like this was the Pope1. Rather, the message from most world leaders, best-case, has been closer to "please listen to me and you can go and eat at restaurants again and we can all kind of agree that this is over now". There were obvious political reasons that this was the message we ended up getting - if your job depends on you getting elected, you'll naturally be reluctant to say things like “we kind of brought all of these bad things on ourselves and we are really going to have to change things around here” - but the easier message we got also led us to this world where, you know, the mass casualty event is still happening.

That's why it's so striking that "we deserve this, and to be honest, we probably deserved worse" is basically what Abraham Lincoln, our least-bad president, said during his second inaugural address, as the Civil War was ending:

"The Almighty has His own purposes. "Woe unto the world because of offenses for it must needs be that offenses come but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh." If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which in the providence of God must needs come but which having continued through His appointed time He now wills to remove and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him. Fondly do we hope - fervently do we pray - that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago so still it must be said 'the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.'"

The war was brutal and bloody, it lasted years longer than anybody thought it would, seven hundred thousand soldiers were dead, and Lincoln got up in front of the country to say that if God had killed more of us, He would have been right to do it, as retribution for our history of slavery. The best that we could do now - you've seen how this speech ends if you have ever been to the Lincoln Memorial or seen that movie with Daniel Day-Lewis - is to try and ease the suffering of the people around us:

"With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in: to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

Lincoln was killed forty-one days later, and endures today as the mythic figure about whom more books have been written than any other American in history. One of those books won a Newbery. So how do you introduce a child to Lincoln, what he was like, and what he did?

Look, I grew up in Illinois, I learned plenty about Abraham Lincoln when I was a kid. We all know the main points of his mythology. He came from nothing and grew up in a log cabin. He basically taught himself to read, and eventually to practice law. He had this famous folksy wit and love for storytelling. He lost a lot of elections and had several failed business ventures before winning the presidency in 1860, becoming the first president from the recently-formed Republican party. Then states in the south broke off to form the Confederacy and Lincoln led us through he Civil War to keep the union together and eventually inspire Titus Andronicus' best album. He ended slavery permanently through the Emancipation Proclamation and eventually the thirteenth amendment. Now he's remembered as one of our greatest presidents, if not the greatest.

Those are the parts of the story that everyone learns in grade school, at least in Illinois. But there are other parts that you don't learn until you're older, and like most Dads, I am always fascinated when I learn more about Lincoln. I've been to his presidential museum twice. My dad once got me a collection of his writings as a gift (true Dad Reading). I've read through all of the Lincoln-Douglas debates multiple times. Here's what you learn once you get past the mythology: Lincoln did have a folksy wit, but he was also a weird sad dude to be around a lot of the time, and probably had clinical depression or something similar. He did end slavery, but not right away; not only was he very upfront about his views on the inferiority of black people, but he also only freed some slaves with the Emancipation Proclamation, because the Proclamation had very specific political, military, and economic objectives. And he is remembered as one of our greatest presidents (I think this is still true in 2022?), but while he was actually president, he was hated by basically everyone, and not just the confederate soldiers; Americans still in the union thought he was a butcher sending their kids to die in a needless war rather than letting the secessionists go, union generals like McClellan were actively undermining Lincoln's command, and Republicans in Congress thought he wasn't doing enough to finally end slavery. One of the more entertaining exhibits at the Lincoln Presidential Museum in Springfield, IL is the collection of political cartoons from the 1860s showing that everyone really hated this guy, and somehow each of them hated him for a different reason.

Russell Freedman's 1988 medalist Lincoln: A Photobiography, to its credit, does not present only the popular myths about Lincoln. It certainly includes Lincoln being a weird sad dude, including his famous quote after his first breakup with Mary Todd that "I am the most miserable man living. If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would not be one cheerful face left on earth," which of course was included in a later Dashboard Confessional album (that's a joke) and the aforementioned Titus Andronicus album (that's not a joke it's actually on the album).

Here's more Weird Sad Dude Lincoln:

"[Mary] wasn't easy to live with, but neither was Lincoln. His untidiness followed him home from the office. He cared little for the social niceties that were so important to his wife. He was absent-minded, perpetually late for meals…and he was moody, lapsing into long brooding silences."

And here's Wasn't Exactly A Big Advocate For Full Racial Equality Lincoln:

"The issue was not the social or political equality of the races, he protested defensively [during the Lincoln-Douglas debates]. He had never advocated that Negroes should be voters or office holders, or that they should marry whites."

And here's Emancipation As Political Calculation Lincoln:

"Lincoln hesitated. He was afraid to alienate the large numbers of Northerners who supported the Union but opposed emancipation. And he worried about the loyal, slaveholding border states that had refused to join the Confederacy. Lincoln feared that emancipation might drive those states into the arms of the South…Lincoln came to realize that if he wanted to attack slavery, he would have to act more boldly."

And here's Lincoln That Nobody Liked No Not Even In The North:

"Antiwar feelings were boiling over. Early in 1863, Northern Democrats launched a peace movement to stop the war and bring the boys home…they attacked Lincoln's policies right down the line - the draft, the military arrests the use of Negro troops, and above all, the Emancipation Proclamation…that summer, violent draft riots flared up in several Northern cities. In New York, a rampaging mob burned down the draft office."

So a reader gets plenty of introduction to the more commonly known facts about Lincoln, but Freedman is sure to include an introduction to the more complex figure as well. The main hook for his biography, though, is that it's a photobiography. Freedman includes photographs from the era on practically every page, with a special focus on portraits of Lincoln from across his life. You probably know what he looked like, as he was one of the most photographed Americans of his century, and you probably know that he aged very noticeably over the course of his very trying presidency. A reader would get introduced to that as well.

But there are other photographs, ones I hadn't seen before, that resonated with me far more than the portraits of Lincoln, and I'm not just talking about this wanted poster for an escaped slave that seems completely useless for identifying someone if you're already a huge racist:

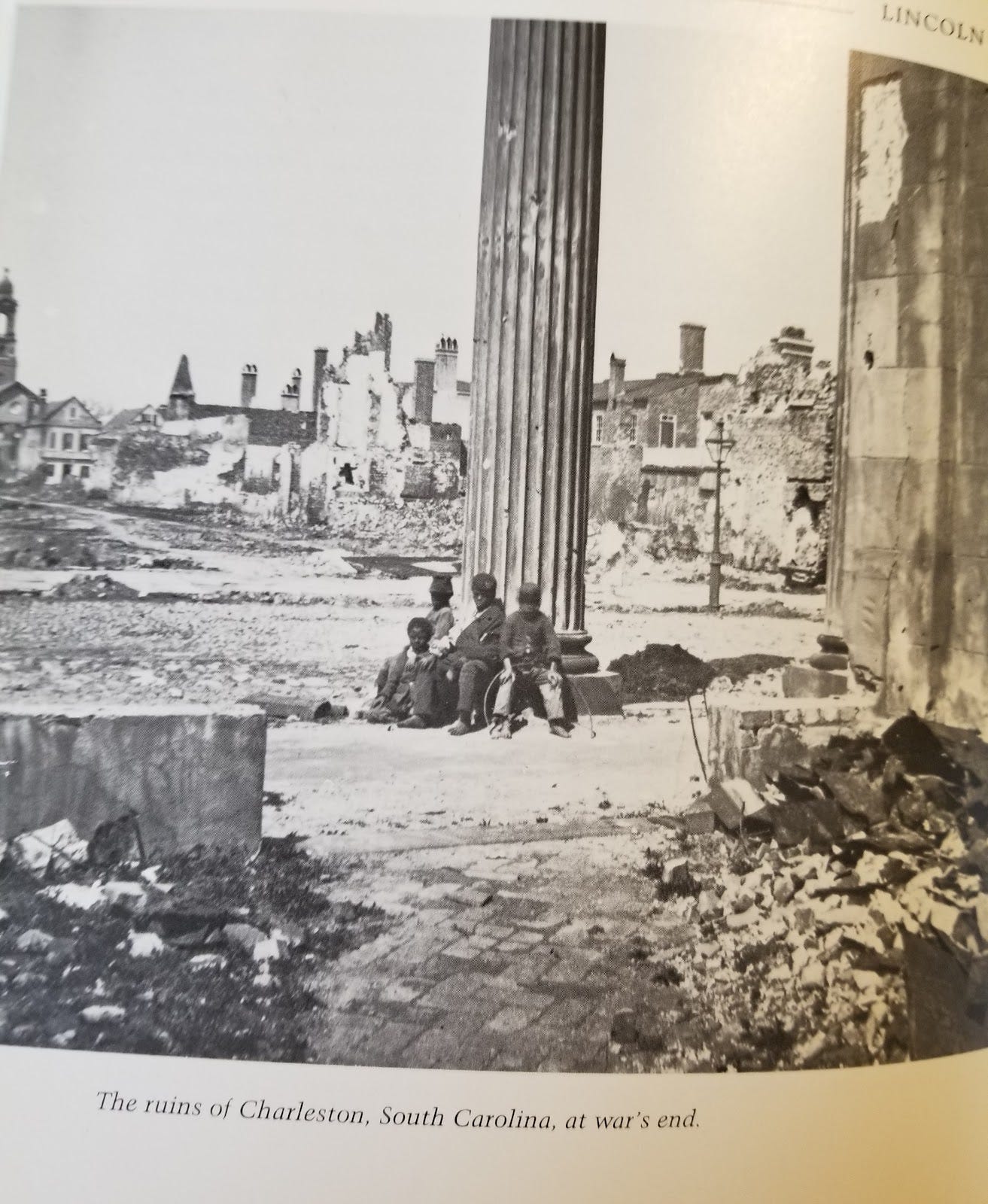

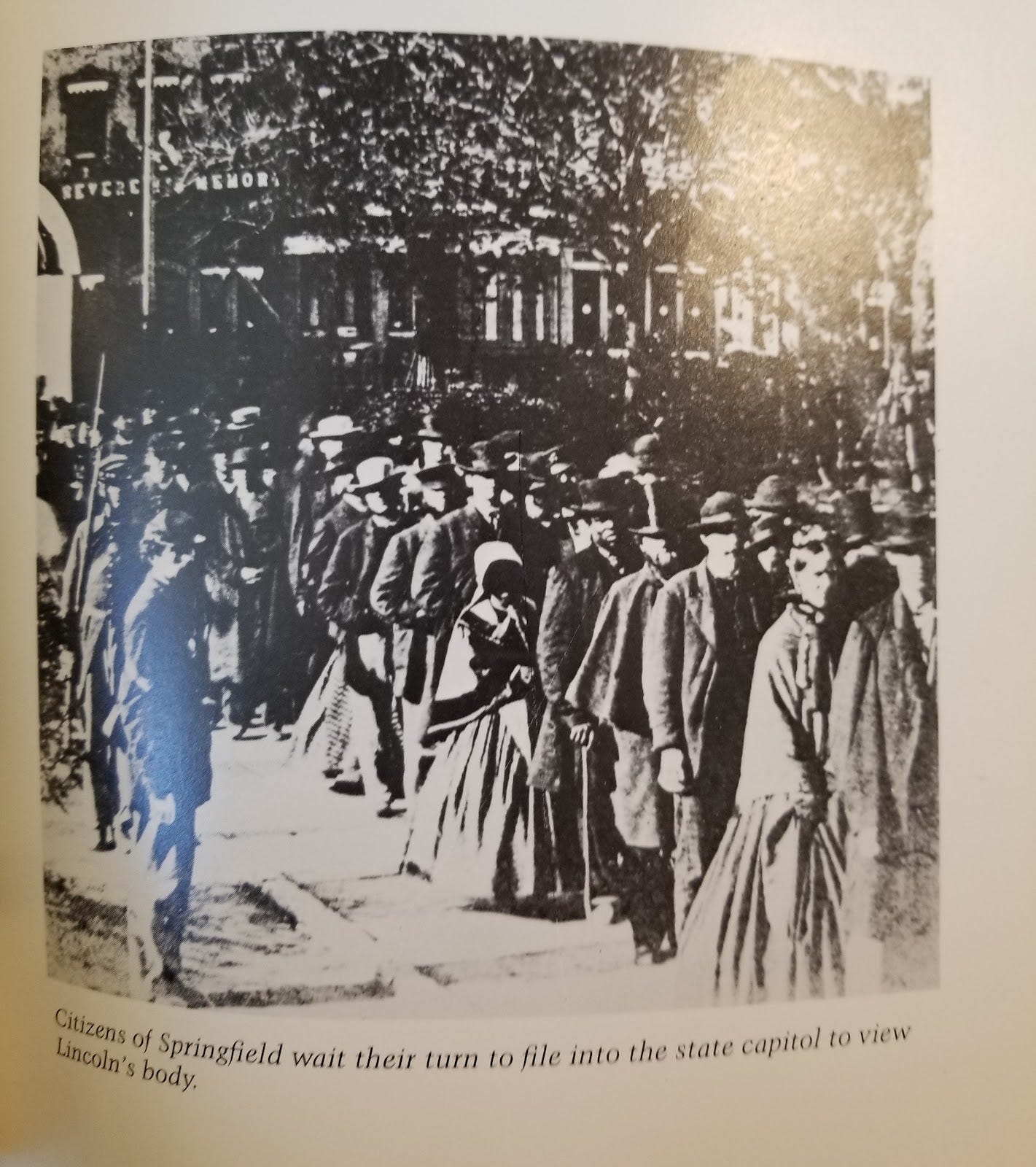

What actually resonated with me were the photographs of cities like Charleston that were levelled by the end of the war, and how exhausted and defeated everyone must have felt by 1865, with their homes destroyed and their families dead, as the president gave his second inaugural address and told us that all we could do now was try to ease each other's suffering. And was resonated with me was the photograph of the throngs in Springfield lining up to see Lincoln's body return home, the people who heard that speech, found a little bit of hope in it, and had just lost the man who promised to lead us through that new era.

There's a story about Lincoln in Freedman's book that I hadn't heard before: he commuted death sentences for Union deserters so much that his generals got annoyed with him:

"He looked for excuses to pardon soldiers. He was reluctant to approve the death penalty…'The generals always wanted an execution carried out before it could possibly be brought before the president,' a friend observed…Lincoln referred to himself as 'pigeon-hearted.'...when he could think of a good reason to pardon, he pardoned, saying, 'It rests me, after a hard day's work, that I can find some excuse for saving some poor fellow's life.'"

Lincoln, on occasion, tried to show mercy to people. That's better than most of us get to do. And Freedman's book works as a child's introduction to Lincoln because it gives you all of the famous facts but makes it very clear that this was a complicated man in a complicated time making decisions for complicated reasons. He was not a perfect person with perfect judgement that everyone loved. But imperfect people with imperfect judgement that aren't widely loved can still make the right decisions if they care enough about acting "with malice toward none, with charity for all".

What's the right way to introduce a child to Lincoln? Whatever it is, I would make sure to also include that second inaugural address, as Freedman does. Whatever my kids learn about Lincoln, his humble beginnings or hit wit or his political savvy, I'd want them to know about that speech. I'd want them to know that he saw us through the worst crisis in our history, and when it was over, he was honest with us about how we got there, and he told us to help each other.

Newburied is a series by Tony Ginocchio on the history of the Newbery Medal and a whole bunch of other stuff related to it. You can subscribe via Substack to get future installments sent to your inbox directly. The next installment will cover the 1969 medalist, The High King by Lloyd Alexander.

I wrote about this in a separate piece last year.