I probably would have liked 2022 medalist The Last Cuentista a lot if I had read it as a kid. Apart from some issues with pacing towards the end, it's very well-written, and Higuera builds out her not-too-distant future world very effectively, and the plot twist did genuinely surprise me and, I think, worked for the story.

The premise of Cuentista is this: life on Earth is about to be wiped out by an errant comet, and the human race, in a slightly more technologically advanced future, is scrambling to figure out how to survive. Three massive interstellar transports are loaded up with Earth's best and brightest - which, in practice, means those who can afford to buy passage on the ark while the masses beg to get their children on board - with the plan to go into cryo-stasis and arrive 300 years later at the newly discovered and inhabitable planet Sagan. Our protagonist, Petra Peña, says goodbye to her grandmother - doomed to perish when the comet hits - promises to remember her inventive folk stories, and boards the ship with her scientist parents and her younger brother. When she wakes up, she'll be ready to colonize a new planet, coming off of a ship loaded with artifacts of Earth culture and history, so that, as her father puts it, “It’ll be our job to remember the parts we got wrong and make it better for our children and grandchildren.”

There's only one flaw in the plan: in between the time Petra goes into stasis and the time she wakes up centuries later, a fringe group calling themselves The Collective stages a coup on the starship, kills a large percentage of the other passengers including Petra's parents, brainwashes the rest, mothballs the Earth artifacts, and starts implementing their plan of “we're going to try to do The Giver in space”. Through an oversight, Petra avoided the brainwashing in stasis and, newly awakened, is now pressed to figure out how to blend in with a faceless cult trying to eliminate all differences from society - as in The Giver, everyone is also given medicine to level out their emotions and, presumably, erase their Hornyness - while somehow getting the hell off the ship and onto Sagan, all while grieving her family and her planet and trying to rescue as many of the other child drones as possible.

The Last Cuentista is heavy - extremely heavy. The novel opens with Petra boarding the ark and watching the crowds of masses about to die in a fiery hellscape erupt in riots outside the gates, and things just get more dour from there. The major theme that Higuera explores, of course, is the power of stories, which is a popular theme for Newbery medalists, just like how so many Best Picture winners are about the magic of cinema. Petra connects with her fellow involuntary low-level Collective child drones - bleak by itself! - by improvising on bedtime stories her abuela told her. In stasis, she learned all of the myths and legends of the ancient world by absorbing it Matrix-style, and because she has stories, she has meaning and purpose tied to the inherent goodness of our shared albeit flawed humanity.

It's not poorly-written, but it's not subtle, either. See, in this book, the bad guys are all like this:

“Imagine a world where humans could reach a consensus. With collective unity, we can avoid conflict. With no conflict, no war. Without the cost of wars, no starvation. Without differences in culture, in appearance, knowledge…Today we celebrate our arrival to the new planet. What happened to the former world was not a tragedy. It was an opportunity to leave our past behind. Thanks to the Collective, not a single memory of a world filled with conflict, starvation, or war will find its way into our future.”

And then the good guys, well, they're all like this:

“What the Collective doesn’t understand is by honoring the past, our ancestors, our cultures— and remembering our mistakes— we become better…I am bringing all of them: Mom, Dad, Lita, Javier, and our home. Ben and my crumbling library, deep in my mind. The stories of Lita [the abuela] and my ancestors. I’m bringing them all to this world.”

Like I said, I think I would have liked this one a lot as a kid, mostly for the science fiction concept. Cool, Earth is over but we're running away to another planet and get to rebuild society, but the people who are rebuilding society are doing it in the wrong way and we have to stop them, and there's spaceships and alien flora and fauna and stuff. It's cool! It's original! I mean, it's kind of like The Giver, but that's fine, I liked The Giver, I'd read another book if you told me it was kind of like The Giver. Problem is, there's another book that came out two years earlier with an extremely similar plot and extremely similar themes that is a much better book, mainly because it is - critically - much funnier.

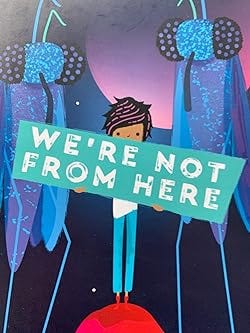

Geoff Rodkey’s 2019 novel We're Not From Here - with a cover blurb by the G.O.A.T. Katherine Applegate! - was recommended by my wife as I was reading Cuentista, specifically by saying “read this book it's a way better version of Cuentista. Cuentista would be a dour dystopian movie and We're Not From Here would be a cartoon.” The book is also about a small remnant of the human race escaping to another planet because life on Earth has ended, in this case due to a nuclear war. The difference here is that the planet is already inhabited; the 2,400 humans that managed to escape are offered asylum on the planet Choom (hell yeah), home to four different races of alien refugees. Choom is a haven for those who have lost their home, and the humans, who are almost out of provisions and oxygen on their ship and on the brink of destroying themselves, go into stasis for twenty years, travel outside of the solar system, and wake up orbiting their new neighbors. Only problem is, in between the time they went into stasis and the time they woke up, a different political faction on Choom swept all of the elections and the new guys in charge absolutely do not want humans there: “We’re terribly sorry. You seem like a nice species. It’s just very bad timing. Best of luck to you, though, have you tried any other planets?”

Our protagonist, the teenaged Lan, is accepted with her parents and sister to be the “test case” for humanity, to try to live on Choom and work there and go to school there in an attempt to convince the billions of alien residents that humans can live there peacefully, so they can secure a spot on the planet for the 2,400 other humans stuck in orbit. But the extremely tense attitudes of the Choom residents are fueled by a media apparatus on the planet that constantly broadcasts old news footage of humans killing each other, as well as a past tragedy caused by an earlier effort to welcome a different refugee species.

We're Not From Here, which I absolutely love, is many things, but it ain't subtle either. This is a story about how we treat immigrants. The humans arrive on Choom only to find mobs of aliens screaming “HUMANS GO HOME!” at them. The hostility that the Choom residents feel towards new arrivals, despite being refugees themselves, is explained like this:

“In most societies there are two basic forces in conflict: progress and tradition. They battle for political control. When progress has the upper hand, there is growth and change. But when that change comes too quickly or causes problems, tradition takes over to act as a stabilizing force. The Zhuri— who rule Choom because they outnumber the Ororo and Krik six hundred to one— are a hive species. Their biology makes cooperation sacred to them. They can’t stand the thought of conflict…Even in a non- hive species, large groups of people— especially angry or frightened ones— behave in ways individuals never would. Sometimes they wind up doing things that are incredibly tragic and stupid. Not to mention violent. That’s what happened here.”

And yet, the heavy sense of gravitas that is all over Cuentista isn't in this novel, in part because you have aliens who look like eight-foot-tall marshmallows walking around. Cuentista, which clearly draws heavily from the YA dystopias of the 2010s, is centered on a protagonist who dutifully takes on the responsibility to save civilization, in the face of death and repression; We're Not From Here, in contrast, is a bonkers comedy of manners, narrated by a teenage girl who, rather than immediately assuming the role of savior, is just bowled over by how absurd it is that she has to go to school with giant bugs and marshmallows and convince them that she's a nice person to have around. And Lan and her fellow human kids are kids - they make stupid comedy videos and quote old sitcom episodes to each other and one of them was a finalist on an America's Got Talent-type show before the nuclear winter hit, and is still bitter about not getting her big break.

In Cuentista, what's going to save humanity is remembering the cuentos from mi abuela and providing a tiny flicker of hope in the grim future. But in We're Not From Here, what's going to save humanity are the only two truly universal languages: music, and dumbass slapstick comedy.

After countless faux pas1, Lan realizes that she is, in fact, occasionally making her alien classmates laugh. Mostly, though, she’s doing it by accident, every time she trips over a classmate’s giant leg and faceplants. But she’d rather have them laughing at her than hating her and thinking they need to expel her from the planet, so she starts doubling down: “They loved it when I tripped yesterday. It was the oldest, dumbest, easiest laugh in the universe. I went for it.” When a classmate flips through Lan’s tablet and discovers her trove of old cartoon sitcom episodes, a black market trade immediately starts throughout the alien city for downloads of human comedy. The ruling government works very hard to suppress art and emotional expression, fearing another tragedy like the last time an emotional species came to Choom. But nobody can resist laughing at an idiot tripping and landing on their face. Lan ends up earning the human race a home on Choom, and thus saving the entire species, by putting together a supercut video of the funniest pratfalls from all of human recorded history. Combined with her sister’s musical performance, the humans do win over the aliens, and live the rest of their days on Choom, setting up as teachers at the cross-species school teaching courses in “music, animation…and improv comedy.”

Don Hertzfeldt's brilliant 2012 animated film2 It's Such A Beautiful Day is, often, bleak and sad and scary and depressing: the stick-figure protagonist, Bill, is dying of some sort of degenerative brain disease and experiencing increasingly bizarre hallucinations and mental breaks as he tries to reunite with his long-estranged and dying father. When Bill does meet his father in a nursing home, they don’t really recognize each other, but, as Hertzfeldt narrates:

“Neither of these two people remember why they're there, or who exactly this other person is. But they sit and they watch a game show together. And when it's time for Bill to leave, he stands and says something beautiful to him.”

What Bill says is “you are forgiven”, which is a beautiful thing to say, but neither party knows what is being forgiven or why it’s being forgiven. But there is something I find very moving - in a melancholy way - about the fact that this moment happened while the two dying men were watching a game show. They were two people who didn't recognize each other and who had no idea how to communicate with each other, and they ended up sharing something so basic, so widely ubiquitous, so comforting and familiar, in what would have otherwise been a miserable moment. That’s the difference, to me, between Cuentista and We’re Not From Here: the idea that all of this cultural detritus, the stuff that isn’t revered treasured family folklore but stupid pratfalls and pop songs, is still inseparable from our shared humanity.

Two books from around the same time talked about the things that can help us narrowly survive the end of the world; maybe it’s folklore, maybe it’s comedy. Maybe it’s what we’re able to forgive in each other and ourselves. I don’t know, I hope one of those works, because I don’t know if the human race is going to last forever.

Bill lasts forever, by the way. That’s how It’s Such a Beautiful Day ends: at the point in the story where Bill would die, the narrator refuses to accept that Bill dies and decides instead that Bill is going to live forever, “exploring, learning, living”:

“He will spend hundreds of years traveling the world; learning all there is to know. He will learn every language, he will read every book, he will know every land. He will spend thousands of years creating stunning works of art. He will learn to meditate to control all pain. As wars will be fought, and great loves found, and lost, and found, lost, and found, and found, and found and memories built upon memories, until life runs on an endless loop. He will father hundreds of thousands of children whose own exponential offspring he will slowly lose track of, through the years. Whose millions of beautiful lives, will all, eventually, be swept again from the Earth. And still, Bill will continue. He will learn more about life, than any being in history, but death will forever be a stranger to him. People will come and go, until names lose all meaning, until people lose all meaning and vanish entirely from the world, and still Bill will live on. He will befriend the next inhabitants of the Earth; beings of light, who revere him as a god. And Bill will outlive them all, for millions and millions of years, exploring, learning, living. Until the Earth is swallowed beneath his feet. Until the sun is long since gone. Until time loses all meaning, and the moment comes that he only knows the positions of the stars, and sees them whether his eyes are closed or open. Until he forgets his name, and the place he'd once come from. He lives, and he lives, until all of the lights go out.”

Two books left.

Newburied is a series by Tony Ginocchio on the history of the Newbery Medal and a whole bunch of other stuff related to it. You can subscribe via Substack to get future installments sent to your inbox directly. The next installment will cover the 2023 medalist, Freewater by Amina Luqman-Dawson.

I had to look it up, but this is the correct plural, it’s spelled the same as the singular.

I wrote this essay months ago, so I didn’t even learn until last week that he’s got a new film out! That’s awesome! I’ll probably rent it this week!