(part 2 of 4) 1994: THE GIVER by Lois Lowry

From this moment you are exempted from rules governing rudeness. You may ask any question of any citizen and you will receive answers.

Bruce Willis has been dead for basically the whole movie, and when Hailey Joel Osment sees dead people, Bruce Willis has been one of the dead people he can see. Tyler Durden is not a real person; Ed Norton's unnamed narrator has been going through a major dissociative episode and has been imagining Brad Pitt's character and actually doing all of the things that it looked like Brad Pitt was doing. The cutaways in the season 3 finale where Jack has a beard aren't flashbacks, they're flash-forwards to a time after Jack has escaped the island. The bandaged woman getting facial reconstructive surgery is conventionally attractive but she lives in a world where everyone has a weird pig face. Verbal is actually Keyser Sose and has been faking his disability this whole time, and also the actor playing Verbal released three increasingly disturbing Christmas YouTube videos in the late 2010s in which he pretended to be a character from his Netflix show while denying the multiple allegations that he had sexually abused minors. The gas station owner with the rebate program in Glendale has been regularly drinking his grandson's piss because he thinks it's a homeopathic remedy.

These are seven of the eight greatest plot twists in history. The eighth one is that The Giver is in black and white.

I know that sounds weird, but if you've read The Giver, you know exactly what I'm talking about. If you haven't read The Giver, you're wondering how a book can be "in black and white", given that the action of a book takes place inside your head.

Jonas lives in a world without animals, or books, or music, or most individual choice. That's obviously a bleak dystopian setting, but it's also feasible. If you really really wanted to, you could, in theory, build a community that didn't have books or music and that had eradicated animal life. It would be difficult, but with unlimited resources and time, you could pull it off. Other aspects of Jonas's world - all of the land is flat, there's no inclement weather - are a heavier lift, but assuming you had some futuristic technology, you could also make that happen.

But something else is missing from Jonas' world, which is very memorably hinted at early on, as Jonas is tossing an apple back and forth with his friend:

"...suddenly Jonas had noticed, following the path of the apple through the air with his eyes, that the piece of fruit had—well, this was the part that he couldn’t adequately understand—the apple had changed. Just for an instant. It had changed in mid-air, he remembered. Then it was in his hand, and he looked at it carefully, but it was the same apple. Unchanged. The same size and shape: a perfect sphere. The same nondescript shade, about the same shade as his own tunic. There was absolutely nothing remarkable about that apple. He had tossed it back and forth between his hands a few times, then thrown it again to Asher. And again—in the air, for an instant only—it had changed."

So something is off with this apple - various cover designs of The Giver have prominently featured the apple1 - and Jonas notices these strange "changes" in other objects a few other times in the first half of the novel. But finally, during his training, he figures he might as well ask the Giver if he knows anything about this. And here is the answer he gets, which blew my sixth-grade mind:

“How to explain this? Once, back in the time of the memories, everything had a shape and size, the way things still do, but they also had a quality called color. There were a lot of colors, and one of them was called red. That’s the one you are starting to see."

It's hard for me to overstate what an insane moment this is for a young reader. The Giver is explaining that things used to have "a quality called color". Which means that this quality no longer exists in Jonas' world.

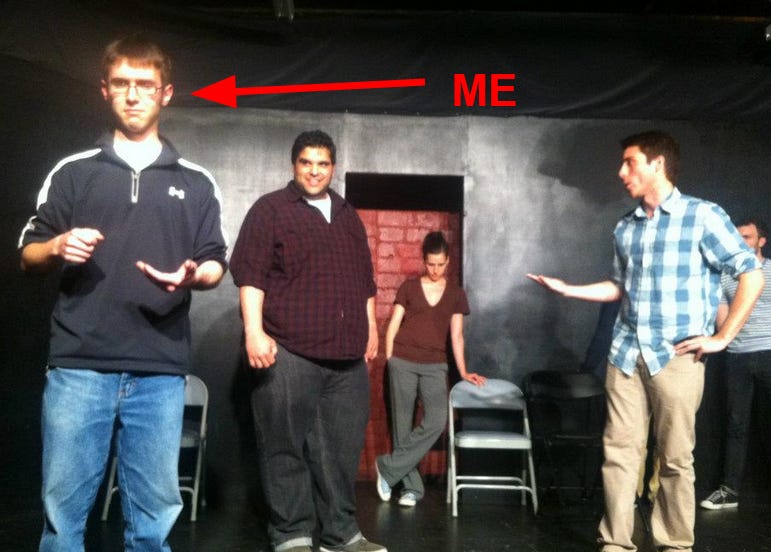

When you create a work of fiction, you are, ultimately, controlling the information that your audience receives and when they receive it. I used to do a lot of performing live comedy, and this happens all of the time in improv where you don't have sets or costumes or props and have to help the audience process all of that using only your words; in fact, one of the things that makes an audience laugh, like physiologically laugh, is when they're given just enough information to rapidly fill in a whole bunch of new information themselves. Anyways, here’s me doing it like ten years ago in a black box theater at 11pm on a weeknight for an audience of like eight people, I believe I am serving myself at a buffet in this scene:

I remember, very specifically, another scene where I and a scene partner were acting out a very sad breakup, when another one of my teammates walked into the scene and told me "Frank? It's your turn to bowl next." And that made people laugh, because now they were filling in that everything they had just seen was actually at a bowling alley, they had mentally filled in all of the dismal setting - the stale cigarette smoke, the flat soda, the flickering fluorescent lights, the goofy shoes - and they were laughing because having a breakup while on a date at such a sad place was funny, and they were also laughing because they were anticipating that we were going to continue acting out this awkward scene while also having to pantomime-bowl at the same time. They processed this high volume of information in a fraction of a second, and filling in that much information that quickly made them laugh. They got one line, and everything they had already seen snapped a little more into focus, and they looked with anticipation towards what they were going to see next. To be clear, I'm not saying this was a brilliant scene, just that it's an illustrative example of the mechanics of comedy and fiction. My ability to explain how comedy works in excruciating detail has presumably contributed to my never having an actual career in comedy.

So what did we get from the Giver's reveal that color no longer exists in this world? It snaps everything that came before into sharper focus: all of the things that you had read in the first half of the novel, all of the things you imagined in your head - Jonas' conversations with his family, the ceremony for twelve-year-olds, the first sessions with the Giver - were in black and white the whole time. A thing that you had assumed about the book you were reading without giving it a second thought - because why would you even consider assuming otherwise? - was wrong, and the blow from that is significant enough to knock the reader off-balance. With every novel you read, you imagine and visualize the action in your head, that's how reading fiction works. The Giver tells you halfway through that your visualization was wrong, not wrong in like a "the good guy turned out to be a villain" way, but wrong in a fundamental way that you never could have guessed, wrong in a way that runs counter to how you normally would run a narrative through in your head.

More importantly, this reveal heightens the stakes for what Jonas is up against. We know, by this point, that Jonas' community has eliminated books and music and animals and weather and hills, so they have a tremendous amount of power. We'll later learn that they've been euthanizing everyone in the community who deviates from their rules, so they have a scary amount of coercive power. But these are all things I can kind of imagine and process in my head. At this key point in the novel, though, we learn that they can literally drain the color from the world. They never explain how this is done, and they don’t have to. They have the ability to do something that has never been done and that none of us can imagine. Whatever power that is, I am now very frightened for Jonas to be up against it.

Part of the reason I still find this plot twist so powerful is that - maybe this is obvious, but it's worth saying - a book is really the only medium where you can pull this off. You can’t do a stage show of The Giver and reveal halfway through that everything the audience just saw was actually black and white (although there is a stage play adaptation of The Giver). You can’t do a graphic novel of The Giver and reveal halfway through that everything the reader just read was actually black and white (although there is a graphic novel adaptation of The Giver). You can’t do a film of The Giver and reveal halfway through that everything the audience just saw was actually black and white (although people tried to make The Giver into a movie for years and Jeff Bridges eventually did, and it received a 35% score on Rotten Tomatoes). In all of those media, it’s going to be obvious right away whether you’re looking at a world that is in black and white.

Going back to my stupid bowling alley scene for a second: the laugh is not because of the bowling alley itself. If we had done that scene as a filmed sketch, shot on location at an actual bowling alley, we wouldn't have gotten that laugh. The laugh came from the fact that the audience didn't know we were at a bowling alley and then suddenly learned that we were at a bowling alley; learning that caused them to re-process everything they had just seen and re-adjust their expectations for everything they were about to see, and processing all of that information very rapidly is what got the laugh. The only way that you get that laugh is by doing it in improv, which is a format with no props, sets, or costumes, a format where the only tools you have are words and you use those words to determine what the audience can actually “see”.

Similarly, Lowry is able to effectively bend the constraints of writing a novel - the structure in which you're only working with words, and if you don't write the words, the things aren't there - to her own purposes. In the case of The Giver, those purposes include all of these slow, incremental reveals to build a groaning sense of dread in Jonas' seemingly utopian world. No other revelation is on the scale of the big shocking moment on color, but there are still plenty of unsettling exchanges like one early in the novel where Jonas' sister mentions that misbehaving children were acting "like animals" and the narration notes that "neither child knew what the word meant, exactly, but it was often used to describe someone uneducated or clumsy, someone who didn’t fit in." Nobody in Jonas' world knows what an animal is, and that is a scary thing to think about, just like the implications of women being assigned the job of "Birthmother" or all of the ominous comments around people being "Released" into "Elsewhere", without any further explanation until you're two-thirds into the novel. Later YA dystopian literature - using The Hunger Games and Divergent as prime examples of the 2010s dystopia wave - would just hit the reader with paragraphs and paragraphs of exposition and explanation on the world's history and how everything worked; in the 2010s, the more words you used, the better your “world building” was.

Unlike the dystopian novels that would become popular decades later, Lowry’s writing, especially when building out her mysterious future world, is lean and spartan. Think about the single sentence in The Giver that reveals that nobody knows what an animal is, and how unsettling it feels to read that, and then compare it to this passage from Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games that explains Katniss’ Mockingjay pin, which is 419 words long and meant as an aside triggered by “I looked at a pin”:

"At the last minute, I remember Madge’s little gold pin. For the first time, I get a good look at it. It’s as if someone fashioned a small golden bird and then attached a ring around it. The bird is connected to the ring only by its wing tips. I suddenly recognize it. A mocking-jay. They’re funny birds and something of a slap in the face to the Capitol. During the rebellion, the Capitol bred a series of genetically altered animals as weapons. The common term for them was muttations, or sometimes mutts for short. One was a special bird called a jabberjay that had the ability to memorize and repeat whole human conversations. They were homing birds, exclusively male, that were released into regions where the Capitol’s enemies were known to be hiding. After the birds gathered words, they’d fly back to centers to be recorded. It took people awhile to realize what was going on in the districts, how private conversations were being transmitted. Then, of course, the rebels fed the Capitol endless lies, and the joke was on it. So the centers were shut down and the birds were abandoned to die off in the wild. Only they didn’t die off. Instead, the jabberjays mated with female mockingbirds, creating a whole new species that could replicate both bird whistles and human melodies. They had lost the ability to enunciate words but could still mimic a range of human vocal sounds, from a child’s high-pitched warble to a man’s deep tones. And they could re-create songs. Not just a few notes, but whole songs with multiple verses, if you had the patience to sing them and if they liked your voice. My father was particularly fond of mocking-jays. When we went hunting, he would whistle or sing complicated songs to them and, after a polite pause, they’d always sing back. Not everyone is treated with such respect. But whenever my father sang, all the birds in the area would fall silent and listen. His voice was that beautiful, high and clear and so filled with life it made you want to laugh and cry at the same time. I could never bring myself to continue the practice after he was gone. Still, there’s something comforting about the little bird. It’s like having a piece of my father with me, protecting me. I fasten the pin onto my shirt, and with the dark green fabric as a background, I can almost imagine the mocking-jay flying through the trees."

This does “build the world”, in the sense that I now know more about Panem, but to advance the story so little with such a massive wall of text that stops the main narrative and explains things directly to the reader isn’t exactly what I’d consider exhilarating.

But where Collins and her contemporaries would add to “build their world”, Lowry subtracts. Not just in the comparatively low amount of exposition or description - the character in The Giver who receives the most physical description is the Giver himself, and I’m still not really sure what any of Jonas’ family members look like - but the reason that the world of The Giver feels “off” is specifically because of what isn’t there. Lowry reveals through those choice bits of dialogue or Jonas’ internal monologue - which is never didactically aimed at the reader - that nobody in this world knows what an animal is. Nobody knows what a book is. Nobody knows what hills are, or weather. There are very basic, obvious things that are completely gone in this world, by some method that is never fully explained, and you don’t have to fully explain it to let it unsettle people. As Jonas receives the memories of our world, we learn that, yes, all of these things existed at some point, but the community has somehow, and for some purpose, eradicated them. The mechanics of how it happened aren’t important; all that Lowry needs you to know is that they can do it, and that’s frightening. Lowry's novel is much leaner than its descendants, and still pulled off one of the most memorable plot twists and dystopian details in all of children's fiction. But Lowry also pulled off a feat more impressive than all of that: she wrote a book that can only fully work as a book.

Newburied is a series by Tony Ginocchio on the history of the Newbery Medal and a whole bunch of other stuff related to it. You can subscribe via Substack to get future installments sent to your inbox directly. This is the second of four installments on Lois Lowry's 1994 medalist, The Giver.

Because The Giver has sold millions of copies, it has gone through many printings and a higher-than-average number of cover designs. The thumbnails for most Newburied essays feature the first edition cover designs wherever possible, but each of the Giver essays features a different cover.